In healthcare and pharmaceutical news this week, famed predictor of the subprime mortgage crisis and hedge fund manager Kyle Bass has taken aim at the pharmaceutical industry.

On Tuesday Bass filed his first Inter Partes Review (IPR) petition with the U.S. Patent and Trademark office, challenging claims in one of the key patents protecting Acorda Therapeutics’ (ACOR) product Ampyra from generic drug makers. Ampyra makes up almost the entirety of Acorda’s revenue, generating $366 million in sales last year, and Acorda is guiding for 2015 sales of more than $400 million. ACOR fell 10% after Bass’ petition was made public.

Industry watchers have been waiting for just this. Bass made clear in early January that he would be going after the pharmaceutical industry, and until this week, the question was who he would target first. In a presentation at Skagen New Year’s Conference Bass outlined a plan to invalidate the patents protecting major pharmaceutical products, a plan that he believes will cut drug costs to consumers while benefiting those positioned to profit from the falling stock prices of pharmaceutical companies.

The working assumption among investors is that Bass is betting against his targets directly by shorting their stock or buying/selling options, possibly even being positioned long generic drug companies. Business Insider reports that Bass is currently raising capital for the pharmaceutical fund.

In a presentation titled “The US Has A Drug Problem” Bass explained in January that he and his fund, Hayman Capital, would target more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies with a combined market value of $450 billion. Bass planned to use a relatively new patent re-evaluation process called an Inter Partes Review (IPR), which emerged with the America Invents Act in 2012. Under the process, a third party can request that the USPTO review any unexpired patent, without going to court. It’s essentially a mini trial process, with the petitioner (in this case, Bass’ newly created Coalition for Affordable Drugs, or ADROCA) able to submit prior art that could invalidate certain claims of the patent in question, and an ensuing back-and-forth between the challenging and defending parties.

An IPR is particularly attractive because the process is relatively quick. Challenging a patent through the traditional court system is an expensive process and can take years to finalize. An IPR trial is complete twelve months after its institution (an IPR is not instituted unless the director determines that there is a reasonable likelihood that the petitioner will prevail with respect to at least 1 of the claims challenged in the petition) and should take no more than 18 months from the day the petition is filed.

Bass will most likely continue to go after mid-size drug companies that are dependent on a handful of drugs – or a single product – for the majority of their revenue, like Acorda

Our view? Bass’s approach may be more bark than bite.

Lets take a bird’s eye view. Generic drug companies have built their entire business on this approach: challenging the patents behind lucrative drug products. The IPR process is still relatively new, and generic companies have only recently begun to employ the process, but does Bass really have an edge on generic firms that have decades of experience in the IP field? Not to mention some of the best legal teams that money can buy?Our suspicion is no, but that might not matter from an investor/trader’s perspective.

Where Bass actually has an edge is in his ability to make public his patent challenge process – and profit from it as investors take stock of his findings. In the same way that Bill Ackman and hedge fund Pershing Square methodically dismantled the Herbalife (HLF) business model in 2013 and 2014 (with a yet-undetermined outcome), Bass has a soapbox from which he can lambast his pharmaceutical targets.

He may not actually need to invalidate many (or any) patent claims in order to turn a short-term profit from the strategy.

Briefly, the two full years of outcomes data from previous IPRs do lean in favor of the patent petitioner. Mintz Levin published a summary of this data in October illustrating that “once an IPR has been instituted [again, the PTO has determined there is a reasonable likelihood of unpatentability] the probability that a claim will not survive is 48 percent, essentially a coin flip.” Taking it a step further, however, Mintz Levin looked at the outcomes of cases in which the PTO reached a decision on patentability on a per petition basis. Of 66 IPR proceedings on which the PTAB reached a patentability decision, all claims were deemed unpatentable in 50 cases, while six cases were deemed completely patentable and claims in 10 cases had mixed results (some claims patentable and others unpatentable).

“Put another way,” wrote Mintz Levin, “when the patentability of claims challenged is determined on a per petition basis, in nine percent of petitions all claims were deemed patentable, in 15 percent of petitions some claims were deemed unpatentable, and in 73 percent of petitions all of the claims were deemed unpatentable. It therefore appears that once the PTAB [Patent Trial and Appeal Board] gets involved, the chances that the challenged claims will be struck down rises precipitously.”

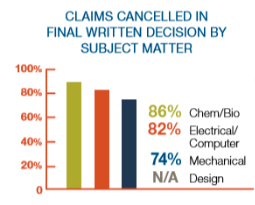

More recently, Harness Dickey illustrate that chemistry and biology claims are more likely than any other segment to be struck down:

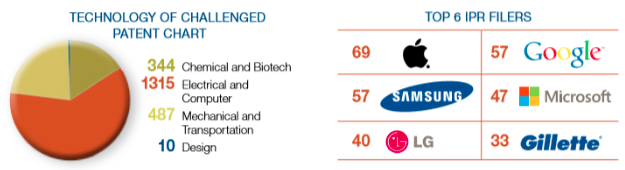

A fun sidenote, Apple (AAPL), Google (GOOG), and Microsoft (MSFT) are the top three IPR filers, historically.

If Bass ultimately succeeds, it is generic drug-makers that will benefit most: companies like Actavis (ACT), Mylan (MYL), and Perrigo (PRGO) are all poised to step in if key drug patents fall prey to the IPR strategy.

Bottom line, I find it hard to imagine that Bass is doing anything that generic drug developers haven’t already considered, but we’ll know soon enough. Within 6 months the PTO will decide whether or not to institute an IPR based on Bass’ obviousness challenge to Ampyra’s 8,663,685 claims. If it does, two years of data suggest Acorda is in trouble.