Generic pharmaceuticals are drug products designed to be functionally identical (bioequivalent) to brand name drugs in terms of the active ingredient, dosage strengths, forms, indications, and minimum quality requirements. Individual manufacturers almost never advertise their generic products, as generic drugs must be marketed under their chemical names (e.g. ibuprofen, aspirin, etc.).

The approval process for generic drugs is much shorter and cheaper than that of innovator (brand name) drugs. Since the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Amendments to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, generic manufacturers have been able to rely on the findings from the clinical and preclinical trials that innovating companies – in many cases, publicly traded biopharma or pharmaceutical companies – conducted for the approval of their brand name drugs. This allows generic manufacturers to circumvent the expensive and time-consuming process of independently conducting long and large studies on the safety and efficacy of a drug that’s already FDA-approved. A generic typically takes 2-4 years to develop and move through FDA approval as opposed to the 10-12 years that it takes for an innovator drug. As a result, the significantly lower development costs allow for lower pricing of generics, which are on average 80-85% cheaper than their brand name counterparts. This also means that the entrance of generic challengers cuts sales from a branded drug meaningfully as consumers opt for the cheaper and equivalent alternative/s.

When can a Generic Drug be Marketed?

To protect innovator drugs from extreme price competition from generic equivalents, drug developers obtain patents and exclusivity rights. Patents are filed with the USPTO before and during clinical trials and are typically effective for 20 years from the date of filing, though in the case of a drug product a patent has no practical use until after clinical trials are completed and a drug is approved. All pharmaceutical patents for FDA-approved drugs are listed in the Orange Book database. Any manufacturer that creates a generic of a drug that has an active patent listed in the database would be culpable for trademark infringement and be subject to litigation by the patent holder.

Market exclusivity provides a second and even more rigorous barrier to entry for generic drugs. The FDA grants new drugs, when approved, a period of time in the market in which the FDA will not approve a like-product. This exclusivity period typically occurs concurrently with a new drug’s patent period and can range from 3 to 7 years from the date of FDA approval, depending on the uniqueness and type of drug. While manufacturers can independently conduct studies of a generic equivalent to an innovator drug during this period of excluvisity, the FDA will not approve any drug that relies on the findings from clinical trials of the innovator drug. Under penalty of law, manufacturers therefore cannot sell generics of any innovator drug with active exclusivity.

Our Investors’ Guide to Patents and Exclusivity offers a deeper explanation of FDA exclusivity periods.

Understanding the FDA Approval Process for Generic Chemical Drugs

To initiate the FDA approval process for a generic, the manufacturer must submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Depending on the conditions of the patent for the innovator drug, the ANDA must be filed under one of 4 certification clauses:

Paragraph I – Patent was not submitted to the FDA

One or more manufacturers may file under Paragraph I for the same generic, which will be approved if the Office of Generic Drugs (OGD) confirms that bioequivalence and other standards are met.

Paragraph II – Patent has expired

One or more manufacturers may file a Paragraph II submission for the same generic, which will be approved if the OGD confirms that bioequivalence and other standards are met.

Paragraph III – Patent will expire on a specific date

Tentative approval may be acquired before the patent expiry date once the OGD confirms that all standards are met, but it is not effective until the FDA confirms final approval after the patent expires.

Paragraph IV – Patent is invalid, or the generic does not infringe on the patent

Filing an ANDA under Paragraph IV is called a Patent Challenge and is considered an act of trademark infringement. Tentative approval may be acquired if the OGD confirms that all standards are met, but final approval is not guaranteed.

If the patent holder decides to sue within 45 days upon receipt of notice, a 30-month stay will be granted, during which generic applications cannot be approved unless the court rules in favor of the ANDA applicant. If the judgment is in favor of the ANDA applicant, or if the patent holder does not sue after 45 days, then final approval will be granted.

In addition, the FDA awards a 180-day exclusivity period to the first patent challenger that files a successful ANDA with Paragraph IV certification, and no other generic can be approved until the exclusivity expires. However, the first applicant has a limited amount of time following approval to begin selling the generic, or else the exclusivity right is automatically forfeited.

What About Biologic Generics?

Biologics (or biopharmaceuticals) are drugs derived from natural sources, such as bacteria or antibodies, and include vaccines, blood, allergenics, and gene therapies. Unlike typical drugs, which are chemically synthesized, biologics use large protein molecules from living sources and must be administered via injection or infusion as opposed to oral ingestion. As such, biologics face more stringent standards for drug replication than typical pharmaceuticals.

First, it’s important to clarify that there is no such thing as a “generic” biologic. Biopharmaceutical equivalents are called “biosimilars”, and because of the complex and heterogeneous nature of biologic medicines, biosimilars cannot be identically replicated from their innovator products, though they are highly similar (hence, the name).

Biosimilars were approved only recently in the United States under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Approval requires submitting a biosimilar Biologics License Application (BLA), in which the applicant must demonstrate that there is no clinically meaningful difference in efficacy or safety between the biosimilar and innovator products. The dosage, method of administration, and primary protein molecules of the biosimilar must be identical to the original.

Additionally, a biosimilar product may be further considered “interchangeable” if the applicant can demonstrate that clinical results of the biosimilar are consistently identical to the original by alternating use of the two products in humans. Approved interchangeable biologics may be substituted for their original counterparts by a pharmacist without the intervention of the healthcare provider who prescribed the product.

How do Generics Affect the Market?

The lower price and nearly identical efficacy of generics make them considerably more attractive to consumers than brand name drugs and thus jeopardize the performance of innovator companies’ products. Generics in 2014 represented 86% of all prescriptions written in the United States.

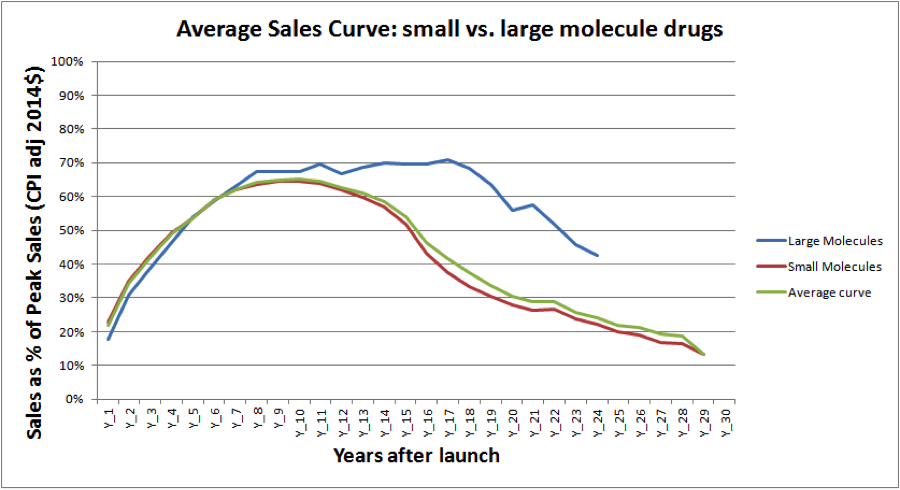

Figure 1 depicts the average sales performance of major brand name drug launches, which tend to reach peak sales by years 10 to 12—around the same time that drug patents typically expire:

Figure 1.

(Source: Evercore ISI)

As the graph indicates, large molecule (biologic) drugs tend to have longer and more consistent annual sales performances than small molecule (chemical) drugs, though this is largely due to the fact that biosimilars have only recently been allowed an abbreviated approval process.

Within a 180-day exclusivity period granted from a successful patent challenge, a single generic product can erode the brand name product’s market share by about 80%. To combat the rapid market penetration of generics following loss of exclusivity (LOE), the innovator company may either heavily discount the price of the brand name or, more likely, sell their own line of authorized generics (AG) at competitive prices in order to recover lost brand share. With only one other competitor during the 180-day period, the latter strategy is often successful in recapturing a significant portion of lost brand share and may even deter other potential patent challenges.