In the last Biotech Basics notes, we covered how to interpret data readouts, and what determines a successful study (details here). Due to the importance of data readouts, biotech companies are incentivized to report positive data, even when it is not entirely accurate.

Below, we’ll cover how data readouts can be misleading and what to focus on to get the real interpretation.

Beware of Study Design: Single Arm, Open Label Trials

Single-arm and open-label studies can be useful in generating hypotheses about the effectiveness of a treatment. In early-stage studies (ie. Phase 1) these designs are generally acceptable. However, in later stage trials (Phase 2 and Phase 3), they have significant limitations that make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Limitations include:

1. Lack of a control group: Single-arm studies only involve one group of participants, without a control group for comparison. This means that it is difficult to determine whether any observed effects are due to the treatment being studied or to other factors, such as natural disease progression or placebo effects.

2. Potential bias & placebo effect: Open-label studies allow both the researchers and participants to know which treatment is being given, which can introduce bias into the study. For example, participants may have higher expectations of the treatment's effectiveness, leading to a placebo effect, or researchers may be more likely to interpret the results in a way that supports their hypothesis.

3. Lack of blinding: In open-label studies, both the researchers and participants are aware of which treatment is being given, which can lead to conscious or unconscious biases that affect the study results. Blinding (or masking) helps to reduce bias by ensuring that neither the participants nor the researchers know which treatment is being given.

Watch For: Single arm, open label studies need to be validated with follow-on trials with more stringent designs, including a control group and blinding. Companies or drug compounds that only run single arm and open label studies are to be avoided. Some compounds will not report similar effects during studies with more stringent designs.

Cherry Picking Data: Post-hoc Analysis

A post-hoc analysis is a statistical analysis that was not specified before the data was seen. Drawing conclusions from post-hoc analysis is a tactic that can be used to make clinical data seem better than it is. It is a form of cherry-picking data that is not part of the original endpoints the study is trying to meet, rather the post-hoc data supports a particular conclusion. This can be done by focusing on a specific subgroup of patients that reported better outcomes than the original population. This tactic can lead to false conclusions and statistical manipulation. The FDA requires predefined endpoints to approve drugs, so post-hoc analysis won’t cut it.

In certain cases, post-hoc analysis can be useful: they help researchers generate hypotheses to test in future studies. For example, in earlier Alzheimer’s Disease studies, mild patients responded better to drug than more severe patients. Based on this post-hoc analysis, researchers could hypothesize that drugs might work better in mild patients, and test that hypothesis in a subsequent study. However, a new Alzheimer study needs to be run to determine this hypothesis.

Watch For: Companies that overlook the original pre-defined study endpoints, and rather focus on post-hoc analysis. This is a telltale sign of goalposts being moved and data being underwhelming.

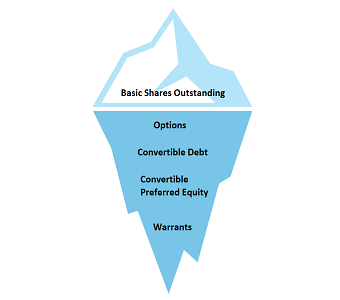

Which Population is Being Analyzed: ITT vs Per-Protocol

ITT means “intent to treat”. This represents all of the patients enrolled in the study, regardless if they completed the study or not. This means that patients who drop out or do not adhere to the study protocol are still included in the analysis. The ITT analysis is considered the gold standard for clinical trials because it preserves the randomization process, which helps to ensure that the groups being compared are similar at the start of the study.

Per-Protocol (PP) refers to the subset of participants who completed the study according to the protocol without major deviations. This approach includes only those participants who received the treatment as intended by the study design, and excludes those who did not adhere to the study protocol or withdrew from the study. PP is used to assess the treatment's efficacy and safety under ideal conditions, however it is not representative of the real-world population, where patients may not always adhere to the protocol, and can underestimate the variability of treatment effects in the general population.

ITT analysis provides a more realistic estimate of the effectiveness of the treatment in a real-world setting. Patients may drop out of a study for various reasons, such as adverse events, lack of efficacy, or personal reasons. By including these patients in the analysis, the ITT analysis provides a more comprehensive view of how the treatment works in the population for which it is intended.

Watch For: Companies will sometimes highlight the outcomes of the per-protocol population to give impression of enhanced efficacy. ITT population outcomes are considered gold standard and what the FDA will look at.

Is Safety Profile Actually “Generally Safe and Well Tolerated”?

Data releases will almost always conclude that a drug is generally safe and well tolerated. Dive deeper into those words to confirm.

Adverse events are any negative side effects that occur during the study. These can range from mild side effects, such as nausea, to more severe events, such as hospitalization or death.

Below is a ranking of adverse events:

- Grade 1: Mild symptoms that require no intervention

- Grade 2: Moderate symptoms with minimal, local, or noninvasive intervention

- Grade 3: Severe or medically significant symptoms but not immediately life-threatening. Hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization occurred.

- Grade 4: Life-threatening symptoms that required urgent intervention

- Grade 5: Death related to adverse event

Watch For: Generally, a Grade 4 or Grade 5 event is a cause of concern, depending on the clinical indication. A late-stage cancer patient will be more prone to serious adverse events, so the benchmark is different than a chronic cough patient. However, if the safety profile is full of Grade 4 and 5 adverse events, the drug is not “generally safe and well tolerated”. It is toxic.

Access This Content Now

Sign Up Now!